Language and shared decision-making

My Twitter timeline recently told me about a new report – Removing barriers to shared decision-making (link here). I’m interested in SDM, so I started reading. I’m sorry to say it will remove no barrier, nor will it help shared decision-making. Here is why.

As a linguist, I was particularly interested in references to language and communication. I found them and….was disappointed. As ever, the document exhorts healthcare providers to use plain language. In fact, when the document refers to language it either talks about plain language or about simplified language. You might think, all good then, innit? Well, not exactly.

I immediately wondered whether the authors of the document spared a thought to the plain-language requirement. As I guess they didn’t, I’ll help. Here is an account of what the campaign for plain English says (link here). Plain language is when you:

- keep your sentences short

- prefer active verbs

- use ‘you’ and ‘we’

- use words that are appropriate for the reader

- [are not] afraid to give instructions

- avoid nominalizations

- use lists where appropriate

And I wonder how many of you can tell me what a nominalisation is, or active verbs (I actually had no idea what active verbs were). Or what a short sentence is. Or, off the top of the head, when it is appropriate to use a list. No? Nominalisation doesn’t really ring a bell? Oh dear, yet, you want you the doctor to write like that?

A little explainer: when the document speaks of ‘active verbs’, it actually speaks of the voice in the clause, distinguishing between active voice and passive voice.

I am being slightly difficult here though. The Campaigners actually explain what they mean and you get to learn about short sentences and nominalisations. But here is the difficult question, how often do you actually stop to think about the grammatical form of what you say or write. When you speak, never, when you write, very very occasionally? Not even that because you still have no clue what nominalisation is. Don’t worry – most people don’t.

All those who insist on writing in ‘plain language’ should do an exercise. Write a letter, whatever letter, and they re-write it according the plain-language rules. And see how much time it will take you. And imagine what kind of burden you will place on the health service.

Should we then give up, you might ask? No, how you communicate is important. But such communication skills must be taught right from the start. And I don’t mean communication skills like ‘lean forward’ or maintain eye contact. Medical students and doctors should be trained in conversing with patients, and assessed not on whether they ask a Calgary-Cambridge question. Rather their patients should be asked to say how they see the conversation. How useful was it? Did they understand, feel stupid or patronised?

Is it difficult? Of course, it is.

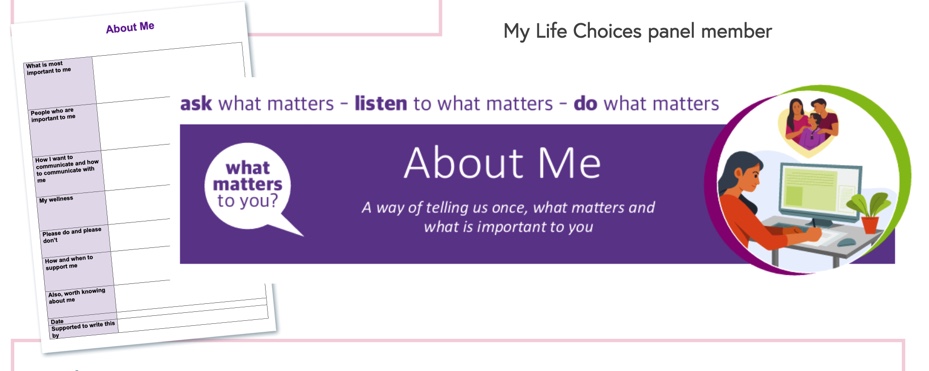

But there is one more thing that struck me in the report. Here is a screenshot of the document:

Patients are supposed to write such things as:

- What is most important to me

- People who are important to me

- How I want to communicate and how to communicate with me

- My wellness

- Please don’t and please do

- How and when to support me

- Also, worth knowing about me

I’ll not mince my words here: it is one of the most unhelpful forms I have seen in my life. It’s dreadful. Do you really want to ask such massive questions as ‘what is most important to me’ on a form that someone might or might not read? Do you really want a person to commit such things to paper?

I marvel at the naivete of the authors who simply think that people, sometimes with extremely complicated and difficult lives, will simply open up and pour their lives onto a piece of paper. Incidentally, I do hope you have noticed how much space is allocated to each task. My longhand writing is quite large, for the form it means a sentence per slot. Yaaaaay!!!

In addition: what on earth am I supposed to say under ‘my wellness’? What am I supposed to say under the communication question (it is a question, isn’t it?)? What’s the difference between how I want to communicate and how I want to be communicated with? I want to phone but you must write?

But what bugs me really is the fact that people are asked to write in the first place. I keep being shocked by the assumption that if I can write, everyone else can as well. Reading and writing are a doddle, piece of cake, anyone can do it. But can they? When you look at adult literacy rates, things are not so rosy. Just under 20 per cent (one in 5!!) adults in the UK have poor literacy skills. Here is an explanation:

They can understand short straightforward texts on familiar topics accurately and independently, and obtain information from everyday sources, but reading information from unfamiliar sources, or on unfamiliar topics, could cause problems. This is also known as being functionally illiterate (link here).

Functionally illiterate, but let’s get to them write to their hearts’ delight! And then, of course, are those who do slightly better. Will they be able to handle the form? Will they be able to write about their wellness, about their communication or what is important to them? You don’t think so? Me neither.

And here we come to the really important point. As you give people a fairly complex writing task, all you achieve is to exclude them. They will not be able to cope. What does it mean? Well, it means that they will either not come again to spare themselves the embarrassment or they will ask someone to fill the form for them. They will relocate the embarrassment.

There is another form, BRAN, another literacy wonder, where the authors can’t decide whether it’s the patient’s voice or perhaps the doctor’s voice. Except it’s really the doctor’s but we just pretend it’s not only.

So, let me offer my usual spiel about language and communication. Things are complex. You cannot simply order people to change their speaking/writing habits just because you like it. This also means writing ‘in plain language’. People will not be able to do it because they have no idea how to. They have no idea what it is. So, you must train them. Both the training and the slower writing (you must take the time) will have significant resource implication.

Moreover, just because a task seems easy and straightforward to you, doesn’t mean it is to me and vice versa. For me writing is easy. I wrote my last single-authored book in about 3 weeks (approx. 80 thousand words). Needless to say, it took me a few years to come to the point of writing but writing itself is easy. I submit my manuscript in version 3. So, my first version is a draft, I read it carefully and make revisions but rarely very substantial. Then I read the revised version, there are a few more revisions to be done and that’s it. Bob’s your uncle, the book’s ready. I once talked to a colleague who told me that they would never submit anything before version 10. That writing for them is like giving birth to a hedgehog. I do hope you see the analogy.

High levels of literacy are commonly assumed without batting an eyelid. Forms or questionnaires are given left, right and centre as if accessing them were so obvious. Yet, it’s not. And it must not be assumed so. Telling people to read and write can be a very inequitable and excluding thing to do. It’s worth bearing this in mind.

What about shared decision-making? Well, nothing. As I said above, the document will do nothing to remove barriers or anything else. Perhaps it’s worth reflecting on it. But there is one quote I would like to end it with:

Letters sent after appointments should address the patient and summarise the personalised shared decision-making conversation that has taken place

That’s the very essence of the piece. The letter is not about any decisions, it is not about what ‘you’ or ‘we’ decided. It is about an impersonal event that has taken place. Why? Because you will be able to tick the ‘job-well-done’ off.

Off to the better future!