Battle of models

I was following the conference on the psychological and social approaches to psychosis (#ISPS2017UK). One of the tweets included Jim van Os’ juxtaposition of the medical recovery model with the personal one. In this post I want to offer comments of a linguist.

Before I start, I’d like to make some reservations. First, I am commenting only on one slide, the model, I’m not commenting on what Prof. van Os said. Second, I want to declare my hand – though my path through matters psychiatric and psychological has been rather messy, I sympathise with van Os’ stance. On the whole, I think that dominant discourses of psychiatry/psychology/psychopathology can be counter useful, though, as I have said a zillion times, it’s good to remember that there is reality beyond language. However, I’m not certain the model offered by Prof. van Os is the way forward.

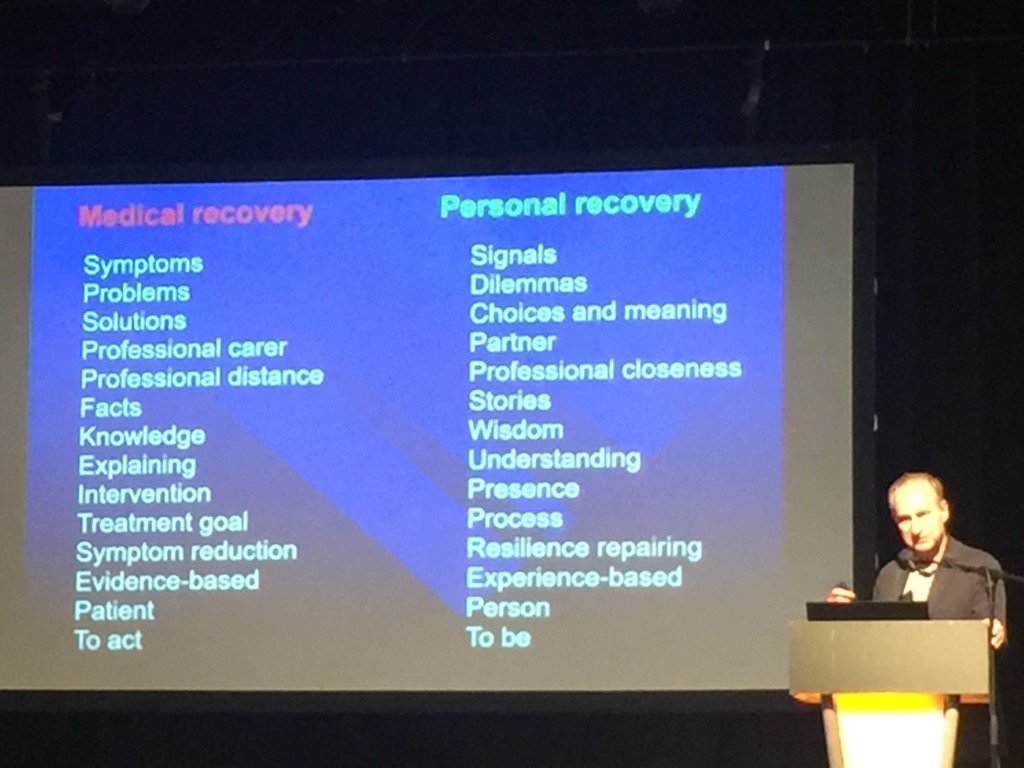

So here is the essence of the two models:

Jim van Os presents 14 pairs of nouns, the way I understand it, those nouns on the right are better, preferable, they refer to recovery in a more useful way. Or perhaps even render reality in a more truthful manner – I don’t know. Below I would like to consider them.

But before I do, I would like make another (by now boring) reference to the fact that of the 14 pairs only 1 contains verbs (yes, ‘explaining’ can be a verb, here it is used as a noun). And to be honest, the 26 nouns are quite disappointing. For linguistically, Prof. van Os hasn’t changed much. Just as the mainstream psychiatry, he also focuses on objects, things to inspect and, possibly, replace. So, on we go replacing objects, a red chair for a blue chair, except we still deal in chairs. How important it is to change the colour of the chair is not for me to say.

After this comment (I will come back as I go along), here are brief comments on the 14 pairs.

1. Symptoms vs signals. The way I see it, this is an attempt to avoid medicalised language. Is it important for me to talk about signals and not symptoms? I’m afraid I doubt it very much. Very quickly, I suspect, ‘signals’ will take over from ‘symptoms’ and every time we’ll use the former word, we’ll need a wink, so that we shall remember that we’re not talking about symptoms. Not at all.

I don’t like ‘signals’ for other reasons – ‘symptoms’ refer to illness, what do ‘signals’ refer to? And please don’t just tell me they refer to life. I really would prefer not to have my entire life pathologised, if you don’t mind, that is. Who will decide that this is a signal, but this is not? No, I don’t believe for one second that it will be only all up to me.

2. Problems vs dilemmas. This is nit-picking, to be honest and I don’t understand it. Are all my problems dilemmas? No, they ain’t, and please, stop telling me what to think of them. Yes, you can say the same about ‘problems’, but the change changes nothing, does it? And could I possibly have a problem and not a bloody dilemma?

3. Solutions vs choices and meaning. We’re here in the realm what I should want, aren’t we? I’m afraid, this is a choice which underscores the power of the shrink. No, I no longer can expect solutions, I can sit with you, kumbaya, and explore choices and meanings… I’d better stop here.

However, obviously, I haven’t got anywhere near the experience of a psychiatrist, yet, when I spoke to men in depression, boy, did they want solutions! Interestingly, the solution was employment, still, it was a solution not a ‘choice’. Choices? Half Twitter is awash with criticising the state of mental health provision for example in the UK, so please, do tell me about my choices. Meaning? Oh, go away.

4. Professional carer vs partner. To be honest, there is so much to write about medical power and how impossible it is to simply get out of its pull that I don’t know where to start. It is very disingenuous to suggest that you can, just like that, become a partner. No, you are not a partner, you will never be a partner and you shouldn’t even begin to suggest that.

5. Professional distance vs professional closeness. Why would you ever assume that I want your closeness? You’re not a friend, you’re not a close one. Don’t you think I should focus on closeness of those around me? Please, don’t impose your closeness on me; distance has its uses. And do remember that after leaving your office, I’m on my own with my demons. As you happily consume the dinner I cannot even hope to afford. Bon apetit.

6. Facts vs stories. Are we really replacing one with the other? Are you really saying that if I tried to kill myself, that’s only a story?

But yes, here van Os comes closest to my heart. Yes, stories are underrated, facts are overrated. But, please, let’s remember that my relationship with you doesn’t end with my story. What if I lie? What if I lie about my suicidal ideation? Will you simply say – that’s a great story?! At the end of the day, you will always have the power to cancel my story (sometimes for good reasons, sometimes not). Don’t ever forget this, please!

7. Knowledge vs wisdom. Please, oh wise one, don’t go there.

8. Explaining vs understanding. Words cannot convey how much I don’t care about your understanding. So, how about noticing me too? I really don’t come to see you so that you understand, even if it is understanding me. I know you’re the most important here, but can we pretend at least occasionally that it’s also about me?

9. Intervention vs presence. Yes, I see what you do, from ‘doing’, you want more ‘being’. And are you really saying that if I want to jump out of the window, you will just offer ‘a presence’?

10. Treatment goal vs process. Why do you want to keep me with you? No, it’s not about the ‘journey’. Well, maybe for you it is, for me it’s not. Really!

11. Symptom reduction – resilience repairing. See point 1.

12. Evidence based vs. experience-based. Can we do both?

13. Patient – person. Can we do both? When will you, medics and, in particular, shrinks, get it that I don’t come to see you because you’re fun to be with. I come for help. That makes me, for me at least, a patient.

I really don’t understand this insistence that social context disappears in psychiatry, and while in shops I am a customer, at work I am a professor, in psychiatry I must be a person. The insistence that I cannot be a patient and I must be a person is only about you and your ego. Nothing to do with me. For me, if I can have a preference, I would just like you to use my surname when you address me. Can your model handle it?

14. To act vs to be. It’s easy for you just to be. I, on the other hand, would prefer if you did something. This is what I come for – so that you help me! If you can’t, tell me you can’t, but don’t just be there.

Here you are. Here is a patient-linguist’s account of the alternative to the ‘medical recovery’. But I want to stress that this account doesn’t mean I like the medical one. Not at all. In fact, I have written quite a lot about discourses in psychiatry and criticised them thoroughly. Here I only want to suggest that the alternative has as many problems. It’s one regime of truth to be replaced by another, equally problematic.

Now, I understand, of course, that the proponents of the ‘recovery model’ can make a nice account of the slide, explaining away the problems I raised. Except that this is exactly what mainstream psychiatry does. They also say that I cannot take ICD or DSM out of context and analyse the language outside how good (as opposed to the bad) psychiatry is actually practiced. And I say: like hell I can’t. your texts give me clear insight into how you want to construct reality for me. But that last two sentences must also apply to the criticals.

Now, I want to finish with a story. Imagine a patient, who does think of himself as a patient, who is very happy to accept his diagnosis (F33). He thinks (well, says) that the diagnosis (for others it’s the dreaded label) explains what happens to him very well. But he refuses – point blank – any suggestion of taking antidepressants. He refuses them because, he insists, the evidence both for biology of depression is sketchy at best, and when you put it next to efficacy of SSRIs, the case for taking them is extremely weak. The problem with the patient is that he jumps between the two models. He cherry picks elements which are useful (from his point of view) in both models and refuses the notion that he must choose between them.

And for me this is the main problem with the battle of the models. As each side shouts that they’re (absolutely) right and the others are (completely) wrong, I wish they noticed there is life between the models. And, returning to linguistics, there will never be a ‘discourse of psychiatry’ which will be useful for all people in all contexts. And I really wish the warriors, the Redcoats of Diagnosis and the Bluecoats of Formulation, understood it. Like many, I for one, really don’t care who will win your war.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.