On evidence for language impact (and its absence)

“The impact of language on people living with long-term conditions: having the rug pulled out from underneath you” says Cochrane UK (link here), promising to offer evidence to support the claim. Have I been wrong, I thought.

Before I tell you what I think about the claim made in the first sentence of this post, let me tell you a story. It’s about one of the enduring stories of my family and was told and re-told by my mother (always with a tangible sense of pride) a zillion times. Here is the story.

When I was about 10, I went on a winter camp. All was going reasonably well until a boy pushed me so hard, I fell over. To make matters worse I fell over on a bedside cabinet, cut my lip and required a few stitches. And here the core of the story starts.

As I was being stitched, so the story goes, my mother phoned the camp office only to find out that Darek was in the ‘operating theatre’. Why did she phone, you might want to ask. Well, something told her to phone. A mother, especially a good one, senses the danger/difficulty her child is in, and reacts instinctively. In the matter at hand, by phoning. Lo and behold, my mother’s child-danger radar proved to work like a charm, as it sensed everything just fine.

Let’s unpick it a little. My mother was talking about impact, there is no doubt in my mind that she believed every word she said. The impact of that “je ne sais quoi” on her was as real the sunrise here in Poland this morning.

But was there impact? Can we trust such evidence of impact? Well, hardly, I suggest. My overprotective mother was phoning every day, the chances of her missing the news were slim. Especially, that she was phoning from work, after my breakfast, the accident had taken place in the morning after getting up, and I was taken to the emergency room immediately afterwards. Did the “je ne sais quoi” have this direct impact on her? I don’t think so.

But, I want to be clear, I don’t want to dismiss the story. It had a significant role in the family narrative, it’s never been questioned by anyone, even though it is unlikely to be true.

I am telling the story because I want to make the point about the difference between impact and declared impact. Just because someone declares that something influenced them (or not) doesn’t mean at all that this is an accurate description of reality. We often claim causality where there is none and vice versa. Cognitive psychology has done more research on faulty reasoning than I care to remember. And so, just because someone says that language has had a profound and life-changing impact on them, it offers no evidence of such impact at all, only of declaration of such impact. But, again, I want to stress – such a statement is not meant to undermine sometimes very strong emotions underlying such declarations.

So, let’s see what Cochrane UK offer by way of evidence of language’s profound impact. And let’s make it clear straight away. Perhaps not surprisingly – they offer not very much at all. They say:

The language used can be stigmatising and lead to the development of labels that live with the person throughout their care experience – ‘poorly controlled’, ‘non-compliant’, ‘low functioning’, ‘high functioning’ are all examples of labels that could have a lasting and detrimental impact on an individual.

Do they provide any evidence? No. As ever, however, ‘language’ is reduced to a few words/phrases, some of them fairly well-rehearsed, as ever, we never learn what actually was said, in what context. The phrases in question seem to push the buttons of impact regardless of the situation they were used? Likely? Not a million years.

For example, was the perhaps unhelpful adjective ‘non-compliant’ used in a conversation with the patient, for example, as in:

You are non-compliant, Mr Galasinski.

What was the context of such an admittedly unlikely statement? Was it for example that Mr G has not been taking his life-saving medication? Was it perhaps another attempt to get Mr G to understand that he was putting his life jeopardy? If so, I would suggest that Mr G got what he deserved and should have been told off some more.

Incidentally, do I believe in “a lasting and detrimental impact on an individual” of the use of adjective ‘non-compliant’? No, I don’t, I’m afraid, but I am remaining open-minded and I am looking forward to the evidence. But no, the notional Mr Galasinski’s claim that ‘non-compliant’ changed his life doesn’t count.

Unfortunately, such discussions are always outside any insight into how language works. Because, you see, if the claim were that it is better focus on actions rather than characteristics, I would say it’s a good point. In other words, instead saying what Mr Galasinski is like, it would be better to say

You haven’t been taking your medication Mr Galasinski, have you?

That’s basically the same message but said focusing on what Mr G does, narrowing the claim to a particular kind of action, rather than on what he (permanently) is. But the point then is not about ‘non-compliant’ or any other ‘label’, but about what grammatical structures to use and how they construct the patient and what they do. Incidentally, the consistent statements about what the patient is like might be more conducive to claims of impact. But that impact would still need to be demonstrated.

Interestingly, Cochrane UK quote an article “Language matters: a UK perspective” (link here), which apparently shows the impact language has on people. I started checking the evidence and, again, I was irritated to see an article like this (link here) quoted as evidence on impact of language. It’s not at all. Another one is on complex intervention in diabetes (link here) and it’s not even about language. Surely, that’s hardly an accident that right at the outset of the first section providing evidence on language impact, the authors of the paper quote texts which provide no such evidence at all.

The authors write further:

in one qualitative study in women with diabetes, communication with their healthcare professional was found to be the most important factor affecting diabetes self-management, with autonomy perceived by the health provider as ‘non-compliance’

How on earth is it on language and its impact? Yes, people find that communication is important – this has been known for decades. So, where is the bloody language impact? I decided to stop. Whenever I start digging somewhat deeper when medicine writes about language, I am left irritated. The authors of the paper are a bit too keen to make their argument stick.

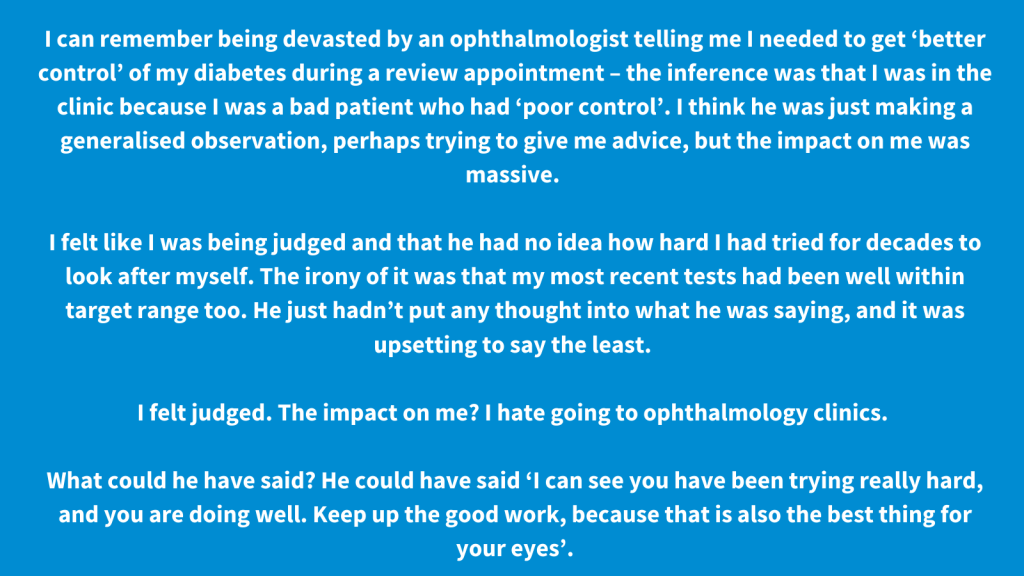

Anyway, let us now have a look at the table below where Cochrane UK offer examples of impactful language.

Once again, I really can’t see ‘language’ there. In other words, as consistently is the case, the table doesn’t present linguistic issues. In the first example, two phrases are identified ‘better control’ and ‘poor control’. Are they really a problem? Or is it really more about the relationship between the clinician and the patient. Note, that the speaker is asking for advice and rejects generalised statements. Is it about language then? Hardly. Would not using the ‘bad phrases’ help? Probably not, if the advice were not forthcoming.

Similarly, in the second and third examples, it is again the position (look at the wok of Rom Harré on speaking positions) the clinician is taking, claiming the right to judge the patient. Here, the patient doesn’t mention any offending words, rather, again, notes a particular way of communicating and the relationship it creates. Would changing words help? Unlikely. The fourth example is a suggestion what could have been said. There are no key words, it’s just wanting a statement of encouragement and support.

All four examples are interesting because they show that what clinicians say is important. But not because of ‘language’, but rather because of how they communicate and what it means. Basically, to stress the point, the example is about a relationship which is forged through what the clinicians say – full of reproach and judgement, with no empathy and support.

You could say, however, that this is what is meant by language. It’s just a shortcut for communication. And, indeed, this is what the rest of the document points to. Except that by consistent insisting on focusing on language, much is missed. How clinicians behave, how they listen, the quality of the voice, eye-contact. The more you focus of ‘language’, the more you miss all the rest. The smile, the handshake, or the receptionist or nurse walking into the room without knocking. And one of my particular irritants, the way furniture is arranged.

And so, I really could not have cared less about what words were used once, when during a conversation where I was told I might have cancer, a nurse barged in three times doing something at the back of the room. I was in tears, and she simply went about her business. And you want me to worry about the phrase ‘poor control’. I didn’t give a damn about the phrase, I wanted a peaceful uninterrupted conversation. Here is my post about this.

This is why I think this constant focus on ‘language’ is unhelpful. It’s not about language. It’s about how we talk to each other, who listens, how we sit, how we look at each other. So, stop this nonsense about ‘non-compliant’. Some patients are non-compliant! Some doctors can say ‘non-compliant’ in a supportive way. What matters much more is what kind of relationship you have with your clinician and what that relationship allows to be said.